So where to begin? What needed fixing? How did we fix it?

Any replacement parts required were unlikely to be found in some spare parts store, so we either had to find the closest possible alternative or manufacture new parts from scratch. Even something as simple as replacement springs required months of following up leads and multiple candidate spring purchases (small runs of designer springs are too financially prohibitive) and testing with samples so as not to introduce a more inferior, or too strong spring into the equation. Here is a brief summary of some of the things we worked on to improve or fix the overall mechanism:

a.)

As one of the white keys had missing ivory on top a suitable replacement in the form of 1 millimetre acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) plastic was sourced. This was about the same thickness as the ivory and had been recommended by a piano restorer that I had made a few inquiries with. Since the use of ivory for piano keys is basically illegal plastic was the only viable alternative. It could be scored to the dimensions required and then snapped at exactly these cuts to make a very accurate replacement. (although a little whiter than the yellowed original)

(It's the A#)

In addition to this, other, loose ivory was re-glued and the keyboard was cleaned removing years of caked on dust and vermin excrement. A combination of rubbing alcohol swabs and slowly applied amounts of toothpaste appeared to provide the best results. An earlier attempt with nail polish remover proved too corrosive to the shiny finish of the ivory.

b.)

Finding suitable springs for the back of the keys proved most problematic. This was largely a trial and error process. Given that the keying mechanism does not need to be as sensitive as a piano's, since a player is not really capable of pianissimo type dynamics on the dulcitone, we felt it acceptable to err slightly with springs that were probably stronger than the originals when they were new. This was guesswork as we had no idea what the action of a brand new dulcitone felt like.

c.)

While a lot of the hammers had felt that certainly showed signs of being snacked upon, they were still in reasonable condition. There was, however, one that had broken right off.

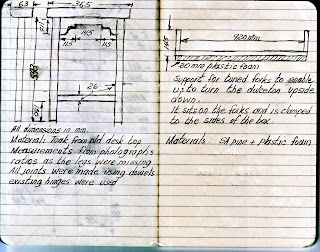

Interpolating the dimensions of the missing hammer by looking at the hammers on either side,

a new core was carved out of teak.

(Notice the slightly elongated base to cater for part of the hammer dowel that was snapped off.)

Felting of piano type hammers involves the use of hydraulic presses capable of exerting 35 tons of pressure in order to pre-shape and glue the felt in low temperature controlled environments. In the absence of this, we sourced 1cm thick dense white felt, cut this to shape and glued it around the teak core with many mini-vices to keep the felt from buckling. A little bit of steam was applied to the felt before hand to make it slightly more pliable.

After assembly, the attack onto the forks was deemed a little 'soft' compared to the other hammers, so a light application of diluted wood glue was applied to the surface which restored some of the 'bite' to the hammer's attack. Job done!

d.)

When the hammers return to rest after being pressed their dowels are pressed against felt of approximately 4mm thick. Much of this felt had been eaten away by vermin. Replacement felt was relatively easy to source and apply. The only interesting anecdote worth recalling is that to retract all 61 hammers simultaneously away from their resting point in order to glue down the felt strip required a 1cm diameter steel rod. A wooded dowel almost snapped under the combined strength of all the hammer and key springs.

Another view of the new hammer and the re-felted surface against the dowels

e.)

This area contains an essential part of the keying and hammering mechanism as the hammers trajectory downwards onto the forks is guided by an ingenious combination of springs, felted pads coated with fabric and a simple cam that governs the exact depth of the hammer strike and controls the retraction of the hammer upon striking the forks so at not to strangle the tone. Some of these were in dubious condition and a number of new fabric coated felts were introduced. Each cam surface was given a coating of graphite powder for lubrication. This stage was particularly time consuming, hell on the back and constantly felt like being both on the performing, and receiving end of a root canal!

f.)

Replacement of all felting cushioning the actual keys as they come into contact with the dulcitone body so as to minimize any unwanted percussive noise. This included the manufacturing of circular pieces of felt needing to be placed around the metal rods which govern the key trajectory. 61 times. Each metal rod, sanded of oxidation and grit to ensure smooth key action. 61 times. Yeah.

g.)

Each damper felt was replaced with 5mm felt. A lot if this fine work (not only to remove the felt but also glue) was performed with a high speed

Dremel tool using a variety of heads. Its doubtful such non-invasive precision could have been performed with anything else.

The damper mechanism itself is initiated upon release of the keys, when two tiny springs bring the damper gracefully down onto the just-stuck, vibrating forks to deaden all tone. Due to years of over-stretching, these tiny springs, I suspect, had become weakened to the point that not all of them came down with sufficient force to mute the vibrating forks. Sourcing springs tiny enough seemed fruitless. Even if we did find some the mechanism would have been rather difficult to get at to do any micro surgery on.

Instead, we opted to place and glue tiny lead fishing weights just above the felt on each of the problematic dampers. In most cases this provided sufficient moment to successfully choke all vibrating forks.

Two different types of weights depending on the severity of the damper spring so as to not unnecessarily overweight the mechanism.

This fix brought about an additional improvement. With all tuning forks properly dampened in their default or rest position, there were less vibrational noises when playing the instrument which would normally be caused by

sympathetic vibration.

h.)

While all the tuning forks were still present, some were rather badly oxidized which affected tone, timbre and tuning. Not being able to do too much about tuning, we opted to very, very carefully clean and polish some of the bad ones which considerably improved the tone and sustain when struck.

Tuning bracelets (added for fine tuning adjustment upon installation) had come loose from the forks and were contributing to sundry rattling. these were firmly reattached with blobs of glue.

Photo depicting rusty tuning fork with loose tuning bracelets, missing springs, eaten hammer felt, not retracting hammers and damper felt about to fall off. The wooden piece with the nails in folds over the forks with the nails keeping the forks apart so they don't bash against each other when being transported.

i.)

A number of the leather fork holders needed to be replaced as the leather itself had hardened or perished to the point where they were providing little support and tension for the forks. This was again a rather laborious process and made harder by the presence of the aforementioned fork tuning bracelets. Suitable screws and paper washers (made from gasket paper material) needed to be sourced and manufactured as there was significant rust and wear to those components.

j.)

The 7 smallest tuning forks had completely snapped off their sheet metal fork lift springs. This was not a trivial salvage job as they were initially riveted onto the forks. Their job was to provide support but also be sufficiently springy to allow the forks to vibrate freely.

First the old rivets were drilled out, then a

machining tap was used to cut an internal thread in the hole of the tuning fork. This would allow a new spring support to be screwed in. This was not easy at all!

Finally, a suitable sheet metal fork lift replacement needed to be sought. Our first thoughts were to use sections from the spiral of a clock spring. This unfortunately did not provide the elasticity to allow the smaller forks to vibrate when stuck. In the end trimmed and shaped sections of sardine can lids provided the solution.

Fresh leather holders as discussed in (i) and forks 1 through 7, from right to left all with their new sardine can fork lift springs.

k.)

All the felt directly below the forks was replaced. This reduced rattling and buzzing significantly.

l.)

The sustain pedal and body of the dulcitone will be discussed in subsequent posts.

EDIT: Parts

1,

2,

4,

5 and

6 of this story

.JPG)